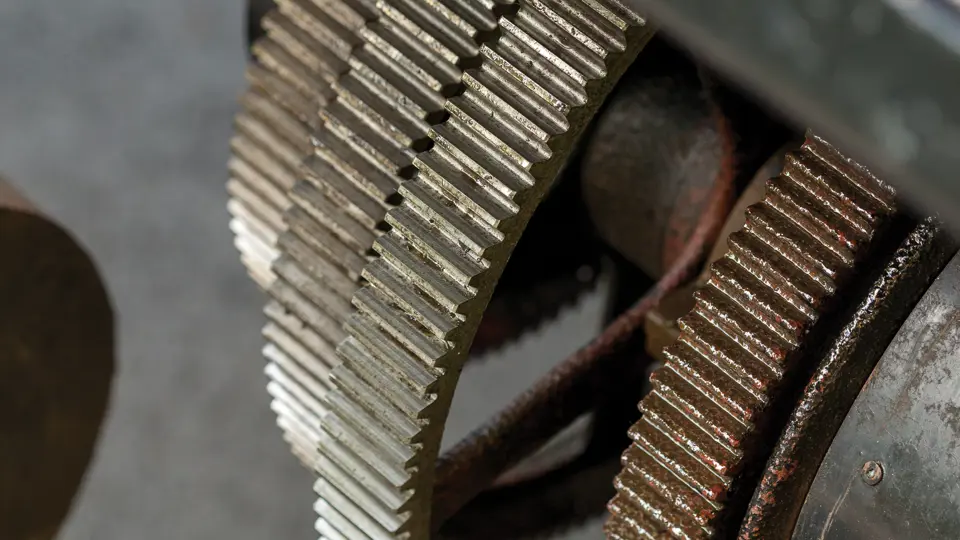

367 cu. in. air-cooled horizontally opposed two-cylinder engine, three-speed transmission with variable-speed magnetic drive, full-elliptic leaf-spring front and rear suspension, and a rear differential brake. Wheelbase: 74 in.

“From Out A Dark Corner Came These Industrial Ghosts”

So read the headline published in The Hartford Courant on September 22, 1963, when the Capewell Manufacturing Company made some unexpected discoveries during a cleaning of their old horseshoe nail plant in Hartford. Aside from about 20 circa-1880s bicycles, commonly referred to as “penny-farthings,” there was a four-wheeled horseless carriage that was built by one of Capewell’s predecessors, the Armstrong Manufacturing Company, of Bridgeport, Connecticut.

It is believed that the Armstrong was built over a period spanning 1894–1845; thus, it existed a year before England would repeal its infamous Red Flag Act. After its completion in Bridgeport, the car was one of six entrants in a race hosted by Cosmopolitan magazine, which ran from the Manhattan Post Office in New York City to the Cosmopolitan offices in Irvington, New York. As was quoted in an extensive piece written about the car by noted English automotive author and historian Michael Worthington-Williams, “The race came off like a Barnum and Bailey circus, with competitors rattling and careening over treacherous cobblestone pavements in a desperate effort to avoid collisions with horse-drawn carriages, cable cars, and (war) veterans dispersing after a parade.”

Shortly thereafter, the car was placed on the market by The American Carriage Motor Company, of New York, likely as a litmus test to help the principals of Armstrong determine the commercial viability of their prototype. After receiving a lukewarm response, it was returned to Armstrong’s Bridgeport factory, where it remained until around 1950, when the firm was purchased by Capewell. The contents of the factory, including the penny-farthings and the Armstrong, were moved to Hartford.

The Armstrong would lay dormant for another 13 years, until newly minted Capewell Vice President Henry C. White would discover the Armstrong during the cleaning he initiated during the slow summer months of 1963. From there, the car was moved into a Capewell employee’s garage in Harwinton, Connecticut, which would be its home until 1995. The existence of the Armstrong was then brought to the attention of the Magee brothers by Dennis David, a local automotive historian. The car spent several years in their collection before being exported to England by Robin Loder, an enthusiastic member of the Veteran Car Club of Great Britain. Loder entrusted the car to restorer Robert Steer, one of the foremost restorers of Veteran cars, who set about restoring the cosmetics of the car, as well as preserving a majority of the bodywork. Steer would also sort all of the intricate electromechanical workings that were devised by the estimated half-dozen Armstrong employees involved in its manufacture.

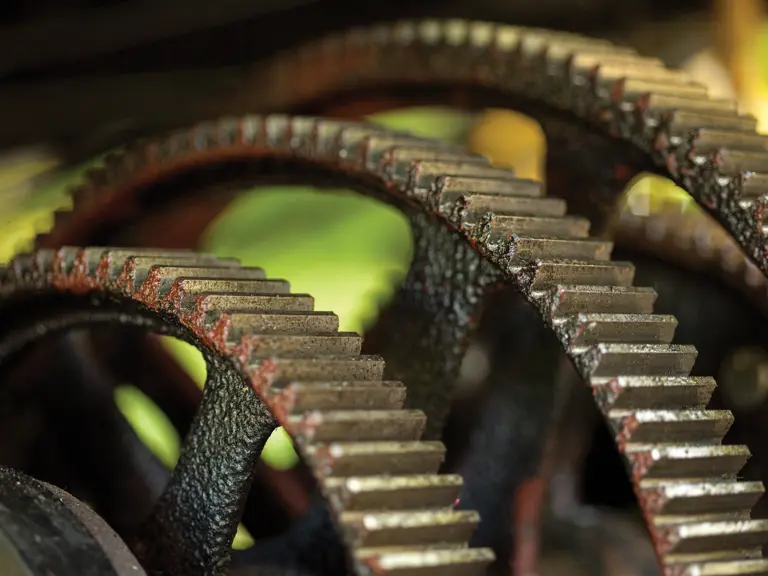

The Armstrong is a display of Yankee ingenuity throughout, and it bristles with features that would not be seen on other production vehicles for many years to come. These included a tubular chassis frame, electric lights, and electromagnetically controlled inlet valves. The car also features an early form of automatic spark control, which was managed by a flyweight governor mounted on the end of the crankshaft. In addition, the Armstrong features a silent electromagnetic starter within the flywheel; Armstrong called it a “commencer,” and it was also found much later on the Mercer Model 22-70 and the Owen Magnetic. The transmission is a three-speed unit with additional variable magnetic drive, which is yet another wonder that preceded the similarly engineered unit found on the Owen Magnetic some 20 years later.

Within the last several years, the car was imported back to the United States, where it was treated to a fresh round of sorting by well-known Brass- and Veteran-era specialist Stewart Laidlaw. This included work on the original electric starter, which is a critical element, as there is no means for hand-cranking, as well as an adjustment of the electrically controlled inlet valves. Most importantly, the Armstrong has been dated by the Veteran Car Club of Great Britain as being manufactured in 1896. This is typical of the conservatism of the VCC, given that contemporary sources indicate the date of completion to be 1895 or perhaps 1894. In any case, the dating certificate is extremely important for its eligibility for entry into Veteran car events around the world, including the revered London to Brighton Veteran Car Run.

Having survived almost a dozen decades and now restored and made functional once again, the Armstrong remains a symbol of the manufacturing ingenuity and forethought in the New World. From a period when there was no “right” way to build a car, many who attempted this feat lost heart or ran out of money long before completion. Many manufactures managed to make crude copies of existing vehicles, and some even made them work…for a few yards.

Even fewer enthusiasts started with a blank sheet of paper, proceeded with their own original design, finished the project, and then had their vehicle running on the highways. The Armstrong was one of these original few.

Please note that this lot will be sold on a Bill of Sale.

| Hershey, Pennsylvania

| Hershey, Pennsylvania